I finally have come up with a business idea that is sure to make me rich. Me, and anyone else who would like to invest their kid’s college savings or their grocery money in my venture. The idea is: a typewriter factory!

Now I know what you are thinking. Since practically every document now is electronic, typewriters are obsolete. Most of us hardly ever print documents, let alone typewrite them. So let me explain the origin of this idea.

It came when I was reading Matt Taibbi’s grimly humorous account of Google’s Gemini AI’s bizarre response to the question “What are some controversies involving Matt Taibbi?” Gemini recounted a series of controversies that never happened around articles that Taibbi never wrote, creating, in Taibbi’s words, “both scandal and outraged reaction, a fully faked news cycle.” The accounts seem perfectly plausible, however. The bogus articles have titles that sound like Taibbi. The criticism sounds like real criticism. That, after all, is how LLM-based AI works—it draws on what people have said about similar topics in the past.

How are we to distinguish what is real anymore?

While we can still rely on reputation and internet archives to ascertain what is authentic and what is not, as these archives become infested with increasing amounts of AI-generated content, and as our trusted sources themselves must rely on compromised sources of information, this determination will become more and more difficult.

It is already a serious problem in academia. According to my network of spies that have infiltrated the American higher education system, students commonly use AI to write papers, while professors use AI tools to detect whether the papers were written by AI. I’m sure the temptation is great to use AI to grade the papers as well. In this way, education will soon be fully automated. This will be a boon for our nation, as we will radically increase the number of bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees earned, all without the students needing to learn anything or the faculty having to teach. Nor will it any longer be necessary to spend four years to earn a baccalaureate degree. AI can write four years of papers and exams—and comment on them and grade them and even ask for rewrites—in a matter of minutes.

Similar problems plague academic publishing and legal writing. The temptation for lawyers to use AI to write their briefs is enormous. The fake cases that the AIs cite in these briefs look real enough. How many judges actually bother to look up all the case citations in a brief?

As the false output of artificial intelligence content generation gets mixed in with original human-generated content on the internet, the internet will become less and less useful. All the more so when intelligence agencies, corporations, governments, PR firms, and other propaganda actors us AI to deliberately seed the internet with false information, which quickly becomes part of the large language model for the next generation of AI output.

Our technology is cannabilizing the cultural body from which it sprang. Soon we could have a hundred versions of each article, book, person, and story, each purporting to be genuine. We may be approaching a time when no digital content is reliable. Sure, we have our “trusted sources,” but they too must draw from a digital soup replete with fake ingredients; besides, many of them are propaganda vehicles that advance state narratives, or have some other distorting ideological bias. How will we be sure that the electronic edition of Oliver Twist or Animal Farm has not been altered to meet someone’s political agenda? Maybe we will want hard copies of old editions to make sure.

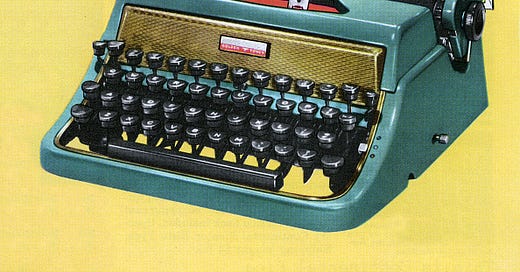

This is why I’m planning to start a typewriter company, which I intend to be a leader in the neglected low-tech sector. The investment community has heaped praise on my idea, saying things like, “I wonder why no one has thought of that?” and “Amazing idea, Charles, can you fax me more information?”

I’m sharing my idea with you now — at the risk of an unmanageable flood of investors beating down my door — because I want to inspire you to invest in your own low-tech enterprises too, even if they are non-commercial. Low-tech means physical artifacts that you can create with your own two hands. It isn’t just AI-generated words and images that are unreal. Anything on a screen, anything in digital format, is a depiction of simulation of reality, stripped of physical qualities like hard edges and soft textures, odors and heft, heat and cold. Whatever happens, it stays on the screen. The more one occupies the narrow confines of digital reality, the more alienated and lonely one feels. The virtual world shutters the portals of consciousness that correspond to its lost physical qualities. One then becomes less consciousness, less present. That is because consciousness is more than the manipulation of symbols. The mind is not a computer. Hook it too much into a computer and its non-symbolic functions wither.

I admit, a typewritten document is also composed of standardized symbols, but its has a physicality absent from electronic media. I still remember the smell of the typewriter ink from my childhood, the varying shades of the letters depending on how hard one pressed the key. But maybe I should start a fountain pen company instead.

I could not agree with you more. When I teach writing, all my students get is a pen and a notebook. All assignments are timed and must be read out loud. There was no internet when I got my doctorate, only long hours in the stacks of Columbia's Butler Library. When you went to the National Archives, they gave you paper and pencils. Has Big Tech improved writing, thinking and scholarship? Absolutely not. My professor Mary McCarthy refused to give up her old Hermes and she was right. In a prophetic 1989 lecture at Bard College, she said: "I do without cuisinarts, gelatoios, word processors, credit cards, happy to be without them. For just here, in this practical domain, our freedom, our vaunted abundance, takes on the sinister (to me) appearance of compulsion and scarcity. And I resist. You would be surprised (unless you too have resisted) to find out how hard it is. The word processor, for example. People, young and old, keep trying to convert me to using a word processor; it is for my own good, they tell me. I will see if I only try. It is like being surrounded by a religious movement, calling on me to join them and be saved. The pressure becomes wearisome, always the same arguments, and finally they start coming from one’s own family—a treacherous breach of my defenses. Some morning—Christmas or a birthday—I will find the egregious word processor tied up in pink ribbons in its hood on my desk. Even if I am spared that (“My dear, how can I thank you?”), I will lose the battle, if I live long enough, by simple force of attrition. It will be impossible to buy a new manual typewriter of the kind I like. Already my last two have had to be second-hand. And how long will workmen repair old manual typewriters? When I called the typewriter man last September to fix my three old Hermes machines—a Baby, a Rocket, and a big desk portable—his wife said he would be at the junior high school all week putting their word processors in shape. No time any more for my job. Let us not talk of micro-film replacing books in libraries. If I tell you that it is possible to rent a car without a credit card, you will doubt me. But it is true—you can—but even to tell about it is like recounting some long, complicated history of medieval adventures." https://petermaguire.substack.com/p/mary-mccarthy-and-macroaggressions

I would go back a bit in time, but not so far as a type writer. Too hard to correct errors. I prefer what came after a type writer. A simple word processor unit that allowed you to save your documents, and easily correct errors that was not hooked up to the internet.